Новости – Digest

Digest

Hostile Voices

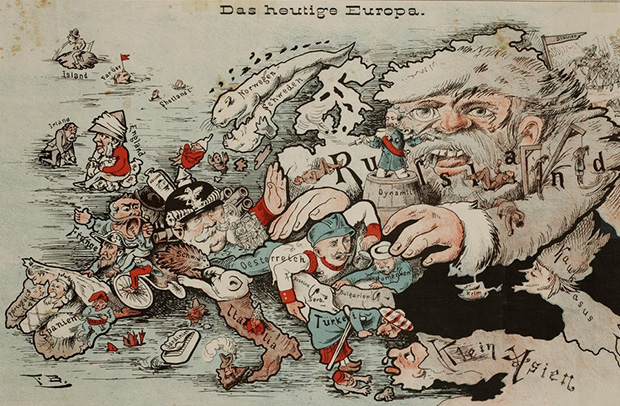

An anti-Russian political caricature published in Germany before the World War I. Photo by: alternathistory.com

The basic principles of anti-Russian propaganda were invented 200 years ago

9 июня, 2016 16:00

4 мин

The Western propaganda against Russia is usually associated with the BBC, Voice of America, Radio Liberty and other representatives of modern mass media. There is nothing new under the sun, however, as the European press had carried out their first anti-Russian propaganda campaigns back in the XIX century. Many of the methods of constructing reality derive from that epoch.

Before the XIX century, there also were foreigners that had written about the horrors of staying in Russia, but that was travel literature rather than false allegations. The stories and tales of Austrian diplomat Sigismund von Herberstein about Russia were nor meant to disgrace the Moscow State, where he had lived for many years. For example, he would tell that certain parts of Russian women froze to the ice in winter, but that was just an exaggerated description of severe weather, not an offence to Russian people. Fiction in the manner of Baron Munchausen had been pretty popular at that time among European readers. However, they were too few to influence politics in any way, so there was no need to create propagandistic myths.

Антироссийский агитпром в Европе XVIII века

Anti-Russian propaganda in Europe in the XVIII century. Photo by: loc.gov

Everything changed about two centuries ago. The educated segments of European society had begun to show discontent over exhausting wars that kings would wage of their own volition. The only way to justify those wars was to depict their foes as the enemies of all humankind, which was exactly what propaganda in newspapers and books was designed for. In the course of the XIX century, Russia had participated in a number of wars; each of those times, European publishing houses would spare neither ink nor paper to convince people that their soldiers were fighting against cruel brutes. For instance, when Napoleon invaded Russia, the French newspaper constructed an image of a wild country that had to be liberated and enlightened. Meanwhile in England, the victories of the Russian army were celebrated. Particularly, one of the caricatures, called Fireman Cossack (reminder of the fire that Moscow had been put to), featured a giant bearded Cossack poking little Napoleon with a pike.

Curiously, despite Russia and England were allies in that war, the Cossack in the picture looked more like a monster than a human being. In fact, in 1813 British journalists were ordered to depict Napoleon’s campaign as bloodbath, where ‘civilized’ French soldiers would meet horrible death from ‘barbaric’ Russians and their mythological protector General Frost. That image of Russian wildlings became one of the central themes of the British propaganda.

The fifth decade of the XIX century was the time of the cold war between Great Britain and Russia caused by the contradicting interests of the two states. The British Empire was anxious about the advances of the Russian Empire in the regions of Caucasus and Central Asia. Both the British Parliament and newspapers launched a campaign to instill anti-Russian sentiments in the society, while British diplomats were trying to convince the Ottoman Empire and European states that Russia intended to annex the straights and expand its territory to the southern shore of the Black Sea. Nicholas I assured Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, that he wanted “no part of the Turkish land”. However, Lord Palmerston, the then Secretary for War, offered the Parliament a different opinion: it would be reckless to believe that Russia was not going to expand in the southern direction.

That campaign reached its climax in the Crimean War. Taking advantage of the recent invention – the telegraph – British journalists would provide latest news directly from the battle field. The most notable of them was William Russel, reporter for The Times, who would praise the bravery of British combatants “under the terrible threat of the Muscovites’ rifles”. Although Russel paid due respect to Russian officers, simple soldiers were presented by him as bloodthirsty brutes. One of his articles told a story of the demise of one of the British officers who had shown mercy to a mortally wounded Russian… and got a mean bullet in the back. British newspapers of that epoch are full of similar descriptions. However, according to the memoirs of European officers published after the war, there had been more atrocities committed by their soldiers. For example, Zouaves – the French elite infantry – had looted both dead and wounded Russian soldiers.

After the capitulation Russel kept on writing in his provocative manner. Even in the Treaty of Paris he found sensational implication: “The sudden friendly affection between the French Emperor [Napoleon III] and the Tzar [Alexander II] is a factor of deep anxiety for those who want to keep peace.” It was obvious that Alexander was more troubled by a crisis in his own homeland than by revisionist intentions, but British newspapers would scare their citizens with the Russian threat until the beginning of the XX century.

Great Britain was not the only country in the time of the Crimean War where anti-Russian propaganda was published. In 1854 a work titled The Picturesque, Dramatic and Caricatural History of Holy Russia appeared in Paris. In modern terms, it was a comic book – a series of panels with amusing drawings and remarks. The aim of the book was to demonstrate what a horrible enemy the French army had had to face. Russia was depicted as a grim land where people were pagans and idiots terrorized by the authorities. The author of the book was Gustave Doré, a young artist who would later leave his mark upon our world by perfectly illustrating Dante’s The Divine Comedy. The future genius was never a Russophobe; he only had had to work for those who were.

In the 1860s, the conflict between Russia and Great Britain for Central Asia reached boiling point. The successful campaigns of the Russian, which had resulted in the annexation of the territory of Turkestan, were reflected in the distorting mirror that was the British press. Those who read them saw Cossacks mutilating pregnant women and dismembering children on the streets of captured cities. For them, the only desire of the Russians was to take all lands and lives up to the shore of the Indian Ocean. Evidently, nothing of that was true. At the same time, the British troops that had fired cannons on the rebels in the capital of Afghanistan were called peacekeepers who had stood at guard of enlightenment and legitimacy. The British journalists could not even pay proper respects to the “White General” Mikhail Skobelev; they had made up a story that Skobelev was not even a true Russian but the descendant of Scottish emigrants with the last name Scobie.

Another skill that the British press of that epoch had mastered was concealment of facts that contradicted the official position of the empire. The atrocities committed by Ottoman soldiers in Bulgaria had been conveniently ignored by the newspapers that were close to the authorities, even as such notable Europeans as Charles Darwin, Oscar Wilde, Victor Hugo, Giuseppe Garibaldi and others had openly criticized Great Britain. The press went as far as calling the cruel suppression of the rebellion a legitimate method of preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. That policy of concealment was denounced by Russian diplomats who had managed to take advantage of the public outrage among the authorities and people of the continental Europe.

The XIX century had witnessed the transformation of the press into so-called Fourth Estate. The methods that had been invented and first exploited 200 years ago were improved beyond measure with the technologies of the following centuries. The construction of reality on demand of those in power has never been so ambitious as it is nowadays.

Translated by Daniil Yakovenko

поддержать проект

Подпишитесь на «Русскую Планету» в Яндекс.Новостях

Яндекс.Новости